Abstract

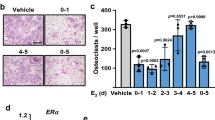

Understanding the mechanisms of osteoclastogenesis is crucial for developing new drugs to treat diseases associated with bone loss, such as osteoporosis. Here we report that the C-C chemokine receptor-2 (CCR2) is crucially involved in balancing bone mass. CCR2-knockout mice have high bone mass owing to a decrease in number, size and function of osteoclasts. In normal mice, activation of CCR2 in osteoclast progenitor cells results in both nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and extracellular signal–related kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) signaling but not that of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase or c-Jun N-terminal kinase. The induction of NF-κB and ERK1/2 signaling in turn leads to increased surface expression of receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK, encoded by Tnfrsf11a), making the progenitor cells more susceptible to RANK ligand-induced osteoclastogenesis. In ovariectomized mice, a model of postmenopausal osteoporosis, CCR2 is upregulated on wild-type preosteoclasts, thus increasing the surface expression of RANK on these cells and their osteoclastogenic potential, whereas CCR2-knockout mice are resistant to ovariectomy-induced bone loss. These data reveal a previously undescribed pathway by which RANK, osteoclasts and bone homeostasis are regulated in health and disease.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Teitelbaum, S.L. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 289, 1504–1508 (2000).

Weitzmann, M.N. & Pacifici, R. Estrogen deficiency and bone loss: an inflammatory tale. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1186–1194 (2006).

Miyamoto, T. & Suda, T. Differentiation and function of osteoclasts. Keio J. Med. 52, 1–7 (2003).

Stepan, J.J., Alenfeld, F., Boivin, G., Feyen, J.H. & Lakatos, P. Mechanisms of action of antiresorptive therapies of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr. Regul. 37, 225–238 (2003).

Tolar, J., Teitelbaum, S.L. & Orchard, P.J. Osteopetrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 2839–2849 (2004).

Choi, S.J. et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α is a potential osteoclast stimulatory factor in multiple myeloma. Blood 96, 671–675 (2000).

Kim, M.S., Day, C.J. & Morrison, N.A. MCP-1 is induced by receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand, promotes human osteoclast fusion and rescues granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor suppression of osteoclast formation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16163–16169 (2005).

Kim, M.S. et al. MCP-1–induced human osteoclast-like cells are tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, NFATc1, and calcitonin receptor-positive but require receptor activator of NFκB ligand for bone resorption. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1274–1285 (2006).

Horuk, R. Chemokine receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 12, 313–335 (2001).

Boring, L. et al. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 2552–2561 (1997).

Charo, I.F. et al. Molecular cloning and functional expression of two monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 receptors reveals alternative splicing of the carboxyl-terminal tails. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 2752–2756 (1994).

Jia, T. et al. Additive roles for MCP-1 and MCP-3 in CCR2-mediated recruitment of inflammatory monocytes during Listeria monocytogenes infection. J. Immunol. 180, 6846–6853 (2008).

Kim, M.S., Magno, C.L., Day, C.J. & Morrison, N.A. Induction of chemokines and chemokine receptors CCR2b and CCR4 in authentic human osteoclasts differentiated with RANKL and osteoclast like cells differentiated by MCP-1 and RANTES. J. Cell. Biochem. 97, 512–518 (2006).

Kruse, K. & Kracht, U. Evaluation of serum osteocalcin as an index of altered bone metabolism. Eur. J. Pediatr. 145, 27–33 (1986).

Russell, R.G. et al. Biochemical markers of bone turnover in Paget's disease. Metab. Bone Dis. Relat. Res. 3, 255–262 (1981).

Lacey, D.L. et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 93, 165–176 (1998).

Li, P. et al. Systemic tumor necrosis factor α mediates an increase in peripheral CD11bhigh osteoclast precursors in tumor necrosis factor α–transgenic mice. Arthritis Rheum. 50, 265–276 (2004).

Tsou, C.L. et al. Critical roles for CCR2 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 902–909 (2007).

Viedt, C. et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 induces proliferation and interleukin-6 production in human smooth muscle cells by differential activation of nuclear factor-κB and activator protein-1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, 914–920 (2002).

Idris, A.I. et al. Regulation of bone mass, bone loss and osteoclast activity by cannabinoid receptors. Nat. Med. 11, 774–779 (2005).

Turner, R.T., Wakley, G.K., Hannon, K.S. & Bell, N.H. Tamoxifen inhibits osteoclast-mediated resorption of trabecular bone in ovarian hormone-deficient rats. Endocrinology 122, 1146–1150 (1988).

Owen, J.L. et al. The expression of CCL2 by T lymphocytes of mammary tumor bearers: role of tumor-derived factors. Cell. Immunol. 235, 122–135 (2005).

Zallone, A. Direct and indirect estrogen actions on osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1068, 173–179 (2006).

Manolagas, S.C. & Jilka, R.L. Cytokines, hematopoiesis, osteoclastogenesis and estrogens. Calcif. Tissue Int. 50, 199–202 (1992).

Manolagas, S.C., Kousteni, S. & Jilka, R.L. Sex steroids and bone. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 57, 385–409 (2002).

Manolagas, S.C. Role of cytokines in bone resorption. Bone 17, 63S–67S (1995).

Cenci, S. et al. Estrogen deficiency induces bone loss by enhancing T cell production of TNF-α. J. Clin. Invest. 106, 1229–1237 (2000).

Wei, S., Kitaura, H., Zhou, P., Ross, F.P. & Teitelbaum, S.L. IL-1 mediates TNF-induced osteoclastogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 282–290 (2005).

Lean, J.M., Murphy, C., Fuller, K. & Chambers, T.J. CCL9/MIP-1γ and its receptor CCR1 are the major chemokine ligand/receptor species expressed by osteoclasts. J. Cell. Biochem. 87, 386–393 (2002).

Breitkreutz, I. et al. Targeting MEK1/2 blocks osteoclast differentiation, function and cytokine secretion in multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 139, 55–63 (2007).

Janis, K. et al. Estrogen decreases expression of chemokine receptors, and suppresses chemokine bioactivity in murine monocytes. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 51, 22–31 (2004).

Arici, A., Senturk, L.M., Seli, E., Bahtiyar, M.O. & Kim, G. Regulation of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression in human endometrial stromal cells by estrogen and progesterone. Biol. Reprod. 61, 85–90 (1999).

Koh, K.K. et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on nitric oxide bioactivity and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 levels. Int. J. Cardiol. 81, 43–50 (2001).

McClung, M.R. et al. Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 821–831 (2006).

Dougall, W.C. et al. RANK is essential for osteoclast and lymph node development. Genes Dev. 13, 2412–2424 (1999).

Kong, Y.Y. et al. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature 397, 315–323 (1999).

Yamada, Y., Ando, F., Niino, N. & Shimokata, H. Association of a polymorphism of the CC chemokine receptor-2 gene with bone mineral density. Genomics 80, 8–12 (2002).

Hayer, S. et al. CD44 is a determinant of inflammatory bone loss. J. Exp. Med. 201, 903–914 (2005).

Parfitt, A.M. et al. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2, 595–610 (1987).

Takeshita, S., Kaji, K. & Kudo, A. Identification and characterization of the new osteoclast progenitor with macrophage phenotypes being able to differentiate into mature osteoclasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 15, 1477–1488 (2000).

Takeshita, S. et al. SHIP-deficient mice are severely osteoporotic due to increased numbers of hyper-resorptive osteoclasts. Nat. Med. 8, 943–949 (2002).

Herault, O. et al. A rapid single-laser flow cytometric method for discrimination of early apoptotic cells in a heterogenous cell population. Br. J. Haematol. 104, 530–537 (1999).

Redlich, K. et al. Repair of local bone erosions and reversal of systemic bone loss upon therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor in combination with osteoprotegerin or parathyroid hormone in tumor necrosis factor–mediated arthritis. Am. J. Pathol. 164, 543–555 (2004).

Mack, M. et al. Expression and characterization of the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CCR5 in mice. J. Immunol. 166, 4697–4704 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to B.R. Binder, L. Bakiri and E.F. Wagner for critical comments and suggestions to the manuscript. We thank the laboratory of P.K. Zysset for their help with microcomputed tomography images as well as C.W. Steiner, M. Tryniecki and A. Raffetseder for their technical assistance and J. Zaujec for performing the ovariectomies. This work was supported by Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant 18223 and by the Center for Musculoskeletal Diseases of the Medical University Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.B.B. designed and performed all experiments and wrote the manuscript; B.N. and R.S. helped with the experiments; M.M. performed CCR2 surface expression analysis; R.G.E. and T.P. performed the biomechanical analysis; O.H. performed the resorption assays; T.M.S. provided and analyzed the Ccl2−/− mice; J.S.S. participated in evaluating data and writing the manuscript; and K.R. directed the project, designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figs. 1–4 (PDF 899 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Binder, N., Niederreiter, B., Hoffmann, O. et al. Estrogen-dependent and C-C chemokine receptor-2–dependent pathways determine osteoclast behavior in osteoporosis. Nat Med 15, 417–424 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.1945

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.1945

This article is cited by

-

Identification of 12 hub genes associated to the pathogenesis of osteoporosis based on microarray and single-cell RNA sequencing data

Functional & Integrative Genomics (2023)

-

Vitamin D Receptor Gene Polymorphisms and Risk of Knee Osteoarthritis: Possible Correlations with TNF-α, Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor, and 25-Hydroxycholecalciferol Status

Biochemical Genetics (2022)

-

Identification and comparison of novel circular RNAs with associated co-expression and competing endogenous RNA networks in postmenopausal osteoporosis

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2021)

-

Inhibition of CCL2 by bindarit alleviates diabetes-associated periodontitis by suppressing inflammatory monocyte infiltration and altering macrophage properties

Cellular & Molecular Immunology (2021)

-

The pathophysiology of immunoporosis: innovative therapeutic targets

Inflammation Research (2021)