Abstract

The development of ways to evaluate interventions that may have an impact on quality of life is a rapidly=developing area of research in clinical oncology, especially within the context of randomized controlled trials. We propose a role for assessments of preferences in such evaluations, including preference studies designed to assess attitudes toward the clinical acceptability of interventions, and preference trials designed to assess choice behaviour in relation to interventions. We suggest that such preference assessments represent a specific case of a more general issue: the need to develop an ‘ethics of evidence’, that is, standards for the creation, assessment and communication of evidence. We then outline a framework within which an ‘ethics of evidence’ might be developed, and suggest that the framework also may provide a useful model for the processes involved in the transfer of research results into clinical practice. As an illustration, we consider the problem of decision making in circumstances where the choice of therapy depends primarily on the patient's own preferences, as, for example, in the choice of mastectomy or breast-conserving treatment in early-stage breast cancer. The long-term goal is to develop criteria which might be used to foster shared rational decision making in such circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

FriedmanLM, FurbergCD, DeMetsDL. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials, 2nd edition, Littleton, MA: PSG Publishing, 1985.

FeinsteinAR. Clinical Epidemiology: The Architecture of Clinical Research. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1985.

AaronsonNK, MeyerowitzBE, BardM, et al. Quality of life research in oncology. Past achievements and future priorities. Cancer 1991; 67(3S): 839–843.

MoinpourCM, FeiglP, MetchB, et al. Quality of life end points in clinical trials: review and recommendations. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989; 81: 485–495.

AaronsonNK. Quality of life research in cancer clinical trials: a need for common rules and language. Oncology 1990; 4: 59–66.

OsobaD (Ed.). Effect of Cancer on Quality of Life, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1991.

MikéV. Suspended judgment. Ethics, evidence and uncertainty. Controlled Clin Trials 1990; 11: 153–156.

Meslin EM. Protecting Human Subjects from Harm in Medical Research: A Proposal for Improving Risk Judgments by Institutional Review Boards. PhD Dissertation. Washington DC: Graduate School of Georgetown University, 1989.

WeinsteinMC, FinebergHV, ElsteinAS, et al. Clinical Decision Analysis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1980.

SchwartzS, GriffinT. Medical Thinking: The Psychology of Medical Judgment and Decision Making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

SoxHCJr, BlattMA, HigginsMC, et al. Medical Decision Making. Boston: Butterworths, 1988.

O'ConnorAMC, BoydNF, WardeP, et al. Eliciting preferences for alternative drug therapies in oncology: influence of treatment outcome description, elicitation technique, and treatment experience on preferences. J Chron Dis 1987; 8: 811–818.

ChadwickDJ, GillattDA, GingellJC. Medical or surgical orchidectomy: the patients' choice. BMJ 1991; 302: 572.

McNeilBJ, PaukerSG, SoxHJJr, et al. On the elicitation of preferences for alternative therapies. N Engl J Med 1982; 306: 1259–1262.

SingerPA, TaschES, StockingC, et al. Sex or survival: tradeoffs between quality and quantity of life. J Clin Oncol 1991 9: 328–334.

MackillopWJ, WardGK, O'SullivanB. The use of expert surrogates to evaluate clinical trials in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 1986; 54: 661–667.

MackillopWJ, O'SullivanB, WardGK. Non-small cell lung cancer: how oncologists want to be treated. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1987; 13: 929–934.

MackillopWJ, PalmerMJ, WardGK, et al. The expert surrogate system. A role for the golden rule in clinical practice. Humane Med 1988; 4: 89–95.

MackillopWJ, PalmerMJ, O'SullivanB, et al. Clinical trials in cancer: the role of surrogate patients in defining what constitutes an ethically acceptable clinical experiment. Br J Cancer 1989; 59: 388–395.

JohnsonN, LilfordRJ, BrazierW. At what level of collective equipoise does a clinical trial become ethical? J Med Ethics 1991; 17: 30–34.

FreedmanB. Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Engl J Med 1987; 317: 141–145.

MooreMJ, O'SullivanB, TannockIF. How expert physicians would wish to be treated if they had genitourinary cancer. J Clin Oncol 1988; 6: 1736–1745.

MooreMJ, O'SullivanB, TannockIF. Are treatment strategies of urologic oncologists influenced by the opinions of their colleagues? Br J Cancer 1990; 62: 988–991.

BelangerD, MooreM, TannockI. How American oncologists treat breast cancer: an assessment of the influence of clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 1991; 9: 7–16.

DeberR, ThompsonGG. Who still prefers aggressive surgery for breast cancer? Implications for the clinical applications of clinical trials. Arch Intern Med 1987; 147: 1543–1547.

BrockDW, WartmanSA. When competent patients make irrational choices. N Engl J Med 1990; 322: 1595–1599.

CiampiA, SilberfeldM, TillJE. Measurement of individual preferences. The importance of ‘situation-specific’ variables. Med Decis Making 1982; 2: 483–495.

AjzenI, FishbeinM. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1980.

WennbergJE, MulleyAGJr, HanleyD, et al. An assessment of prostatectomy for benign urinary tract obstruction. Geographic variations and the evaluation of medical care outcomes. JAMA 1988; 259: 3027–3030.

BarryMJ, MulleyAGJr, FowlerFJ, et al. Watchful waiting vs immediate transurethral resection for symptomatic prostatism. The importance of patients' preferences. JAMA 1988; 259: 3010–3017.

FowlerFJJr, WennbergJE, TimothyRP, et al. Symptom status and quality of life following prostatectomy. JAMA 1988; 259: 3018–3022.

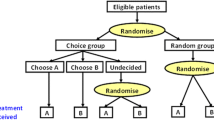

BrewinCR, BradleyC. Patient preferences and randomized clinical trials. BMJ 1989; 299: 313–315.

BradleyC. Clinical trials—time for a paradigm shift? Diabetic Med 1988; 5: 107–109.

WeinsteinMC. Allocation of subjects in medical experiments. N Engl J Med 1974; 291: 1278–1285.

GreenwaldP, CullenJW. The new emphasis in cancer control. J Natl Cancer Inst 1985; 74: 543–551.

FlayBR. Efficacy and effectiveness trials (and other phases of research) in the development of health promotion programs. Preventive Med 1986; 15: 451–474.

TugwellP, BennettKJ, SackettDL, HaynesRB. The measurement iterative loop: a framework for the critical appraisal of need, benefits and costs of health interventions. J Chron Dis 1985; 38: 339–351.

Editorial. Risking less treatment in cancer patients: lessons from germ-cell tumours. Lancet 1988; ii: 430–431.

LasryJCM. Women's sexuality following breast cancer. In: OsobaD, ed. Effect of Cancer on Quality of Life. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1991: 215–227.

FallowfieldLJ, HallA. Psychosocial and sexual impact of diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Brit Med Bull 1991; 47: 388–399.

KiebertGM, deHaesJCJM, van deVeldeCJH. The impact of breast-conserving treatment and mastectomy on the quality of life of early-stage breast cancer patients: a review. J Clin Oncol 1991; 9: 1059–1070.

LiberatiA, ApoloneG, NicolucciA, et al. The role of attitudes, beliefs, and personal characteristics of Italian physicians in the surgical treatment of early breast cancer. Am J Public Health 1991; 81: 38–42.

LiberatiA, PattersonWB, BienerL, et al. Determinants of physicians' preferences for alternative treatments in women with early breast cancer. Tumori 1987; 73: 601–609.

TaylorKM, KelnerM. Informed consent: the physicians' perspective. Soc Sci Med 1987; 24: 135–143.

MarquisD. An ethical problem concerning recent therapeutic research on breast cancer. Hypatia 1989; 4: 140–155.

FallowfieldLJ, BaumM, MaguireP. Effects of breast conservation on psychological morbidity associated with diagnosis and treatment of early breast cancer. BMJ 1986; 293: 1331–1334.

LasryJCM, MargoleseRG, PoissonR, et al. Depression and body image following mastectomy and lumpectomy. J Chron Dis 1987; 40: 529–534.

VanHeeringenC, VanMoffaertM, deCuypereG. Depression after surgery for breast cancer. Comparison of mastectomy and lumpectomy. Psychother Psychosom 1989; 51: 175–179.

LevySM, HerbermanRB, LeeJK, et al. Breast conservation versus mastectomy: distress sequelae as a function of choice. J Clin Oncol 1989; 7: 367–375.

WardS, HeidrichS, WolbergW. Factors women take into account when deciding upon type of surgery for breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 1989; 12: 344–351.

MargolisGJ, GoodmanRL, RubinA, et al. Psychological factors in the choice of treatment for breast cancer. Psychosomatics 1989; 30: 192–197.

WolbergWH. Surgical options in 424 patients with primary breast cancer without systemic metastases. Arch Surg 1991; 126: 817–820.

MunozE, ShamashF, FriedmanM, et al. Lumpectomy vs. mastectomy. The costs of breast preservation for cancer. Arch Surg 1986; 121: 1297–1301.

Van derMaasPJ, DeKoningHJ, VanIneveldBM, et al. The cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening. Int J Cancer 1989; 43: 1055–1060.

WilsonRG, HartA, DawesPJDK. Mastectomy or conservation: the patient's choice. BMJ 1988; 297: 1167–1169.

WolbergWH, TannerMA, RomsaasEP, et al. Factors influencing options in primary breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol 1987; 5: 68–74.

FallowfieldLJ, HallA, MaguireGP, et al. Psychological outcomes of different treatment policies in women with early breast cancer outside a clinical trial. BMJ 1990; 301: 575–580.

FadenRR, BeauchampTL. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

US President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Making Health Care Decisions: The Ethical and Legal Implications of Informed Consent in the Patient-Practitioner Relationship, vol. 1. Washington DC: National Technical Information Service, 1982.

KatzJ. The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. New York: The Free Press, 1984.

VeatchRM. The Patient as Partner. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1987.

AngellM, Patients' preferences in randomized clinical trials. N Engl J Med 1984; 310: 1385–1387.

Till JE. Quality of life measurements in cancer treatment. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Important Advances in Oncology 1992. Philadelphia: Lippincott, in press.

MeiselA, RothLH. Toward an informed discussion of informed consent: a review and critique of the emprirical studies. Ariz Law Rev 1983; 25: 265–346.

WaltersL. Research with human and animal subjects. In: BeauchampTL, WaltersL, eds. Contemporary Issues in Bioethics, 3rd edition. Belmont CA: Wadsworth, 1989: 416–417.

FreedmanB. Scientific value and validity as ethical requirements for research: a proposed explication. IRB 1987; 9: 7–10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Supported by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Grant #806-91-0002), and the National Cancer Institute of Canada.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Till, J.E., Sutherland, H.J. & Meslin, E.M. Is there a role for preference assessments in research on quality of life in oncology?. Qual Life Res 1, 31–40 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00435433

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00435433